<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” Intro ” readability=”38.191640378549″>

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 10 ” readability=”38.5″>

Comet Swift-Tuttle, whose debris creates the Perseids, is the largest object known to make repeated passes near Earth. Its nucleus is about 6 miles (9.7 kilometers) across, roughly equal to the object that wiped out the dinosaurs.

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 9 ” readability=”39.5″>

Back in the early 1990s, astronomer Brian Marsden calculated that Swift-Tuttle might actually hit Earth on a future pass. More observations quickly eliminated all possibility of a collision. Marsden found, however, that the comet and Earth might experience a cosmic near miss (about a million miles) in 3044.

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 8 ” readability=”39.5″>

Perseid meteoroids (which is what they’re called while in space) are fast. They enter Earth’s atmosphere (and are then called meteors) at roughly 133,200 mph (60 kilometers per second) relative to the planet. Most are the size of sand grains; a few are as big as peas or marbles. Almost none hit the ground, but if one does, it’s called a meteorite.

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 7 ” readability=”45.5″>

When a Perseid particle enters the atmosphere, it compresses the air in front of it, which heats up. The meteor, in turn, can be heated to more than 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,650 Celsius). The intense heat vaporizes most meteors, creating what we call shooting stars. Most become visible at around 60 miles up (97 kilometers). Some large meteors splatter, causing a brighter flash called a fireball, and sometimes an explosion that can often be heard from the ground.

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 6 ” readability=”40.5″>

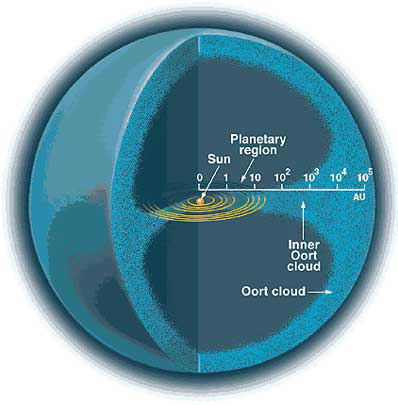

Comet Swift-Tuttle has many comet kin. Most originate in the distant Oort cloud, which extends nearly halfway to the next star. The vast majority never visit the inner solar system. But a few, like Swift-Tuttle, have been gravitationally booted onto new trajectories, possibly by the gravity of a passing star long ago.

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 5 ” readability=”43.5″>

Perseid meteoroids (and if you’ve been following along, you know these are things in space before they hit Earth’s atmosphere) are anywhere from 60 to 100 miles apart, even at the densest part of the river of debris left behind by comet Swift-Tuttle. That river, in fact, is more like many streams, each deposited during a different pass of the comet on its 130-year orbit around the Sun. The material drifts through space and, in fact, orbits the Sun on roughly the same path as the comet while also spreading out over time.

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 4 ” readability=”38.5″>

As Earth rotates, the side facing the direction of its orbit around the Sun tends to scoop up more space debris. This part of the sky is directly overhead at dawn. For this reason, the Perseids and other meteor showers (and also random shooting stars in general) are usually best viewed in the predawn hours.

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 3 ” readability=”38.5″>

Comet Swift-Tuttle was last seen in 1992, an unspectacular pass through the inner solar system that required binoculars to enjoy. Prior to that, it had last been seen in the year it was “discovered” by American astronomers Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle, 1862. Abraham Lincoln was president.

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 2 ” readability=”35.5″>

Swift-Tuttle’s orbit has been traced back nearly 2,000 years and is now thought to be the same comet that was observed in 188 AD and possibly even as early as 69 BC.

<div class=”multiPageItem slideContainer” data-cycle-pager-template=” 1 ” readability=”36.848484848485″>

<div class=”multiPageItem” data-cycle-pager-template=”More“>

Comments are closed.