A curtain of charged particles dances over the snowy mountains of Faskrudsfjordur, Iceland, on March 8, 2012.

Credit: Image courtesy of Jónína Óskarsdóttir, used with permission; rights reserved

When breathtaking auroras wash the sky with color, people around the world can help scientists better understand what creates the beautiful displays and where they appear.

By communicating their wonder through social media and other technology, aurora observers helped improve predictions about where auroras are visible in the night sky through a new citizen science project called Aurorasaurus.

“Using these observations, we can make better short-term predictions of when and where the aurora is for aurora enthusiasts — and scientists,” Liz MacDonald, the founder of Aurorasaurus, said in a statement. New research that analyzes use of the tool suggests that citizen scientists regularly spot auroras closer to the equator than prediction models indicate. Researchers can use that aurora information to better understand the characteristics of geomagnetic storms, which can potentially damage power grids and communication networks. [See the Spectacular Aurora Photos from St. Patrick’s Day Solar Storm ]

Improving predictions

Charged particles streaming from the sun get caught up in Earth’s magnetic field, where they interact with oxygen, nitrogen and other elements in the upper atmosphere to produce dazzling displays of color . Each color is produced as the particles interact with a different element. Those displays, visible near Earth’s poles, are known as auroras.

While particles are always traveling away from the sun in the solar wind, occasionally solar activity produces larger bursts that can amplify auroras, allowing them to stretch farther toward the equator than usual. At the same time, the charged material from the sun has the potential to damage power lines , electrical infrastructures and satellites, causing power outages and communication failures.

In October 2011, MacDonald observed the results of an enormous geomagnetic storm — not in the sky, but through real-time tweets on Twitter. The event was one of the first wide-scale documentations of aurora activity made using social media. Inspired by this, MacDonald founded Aurorasaurus, a project that makes an effort to track auroras as they happen through the Web, apps and social media. When sky gazers alert others to the spectacular show around them, they help improve forecasts for current and future auroras.

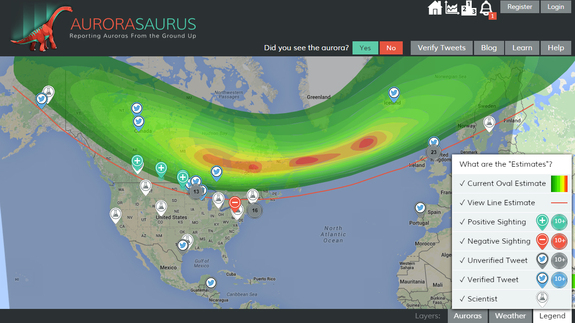

A screenshot of the Aurorasaurus map showing a storm from March 6, 2016. The green, yellow and red areas show the current oval estimate. Green plus signs mean positive sightings; blue Twitter icons indicate verified tweets.

Credit: Aurorasaurus

Credit: Karl Tate, SPACE.com Contributor

Former Aurorasaurus team member Nathan Case, a senior research associate at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom, led a study of 500 aurora observations by citizen scientists during March and April 2015, a period that included one of the biggest geomagnetic storms of the past decade. They found that many people reported seeing the aurora closer to the equator (and thus farther from the poles) than the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s OVATION Aurora Forecast Model had predicted. The research was detailed in the journal Space Weather .

By combining observations from users and verified tweets, Aurorasaurus generates a global map showing auroral visibility in real time. The map includes a “view line,” a region that predicts where a person should see the aurora based on predictions by OVATION, and then expands that line when necessary.

“Without the citizen science observations, Aurorasaurus wouldn’t have been able to improve our models of where people can see the aurora,” Case said in the same statement . “The team is very thankful for our community’s dedication and are excited to have more people sign up.”

In addition to improving aurora detection, Aurorasaurus is also being analyzed by researchers from Pennsylvania State University as a prototype early warning system for emergency responders. When a certain number of people in an area use social media to report seeing auroras, the project sends out notifications to other users to alert them. A similar process could be used in emergency situations.

“The short-term vision for Aurorasaurus is to become an interactive hub for aurora enthusiasts at the intersection of citizens and science,” MacDonald said. “Long term, this engaged community can be sustained and evolve together — and the tools can be expanded to be useful in other disciplines within our technological society.”

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+ . Follow us at @Spacedotcom , Facebook or Google+ . Originally published on Space.com .

Comments are closed.