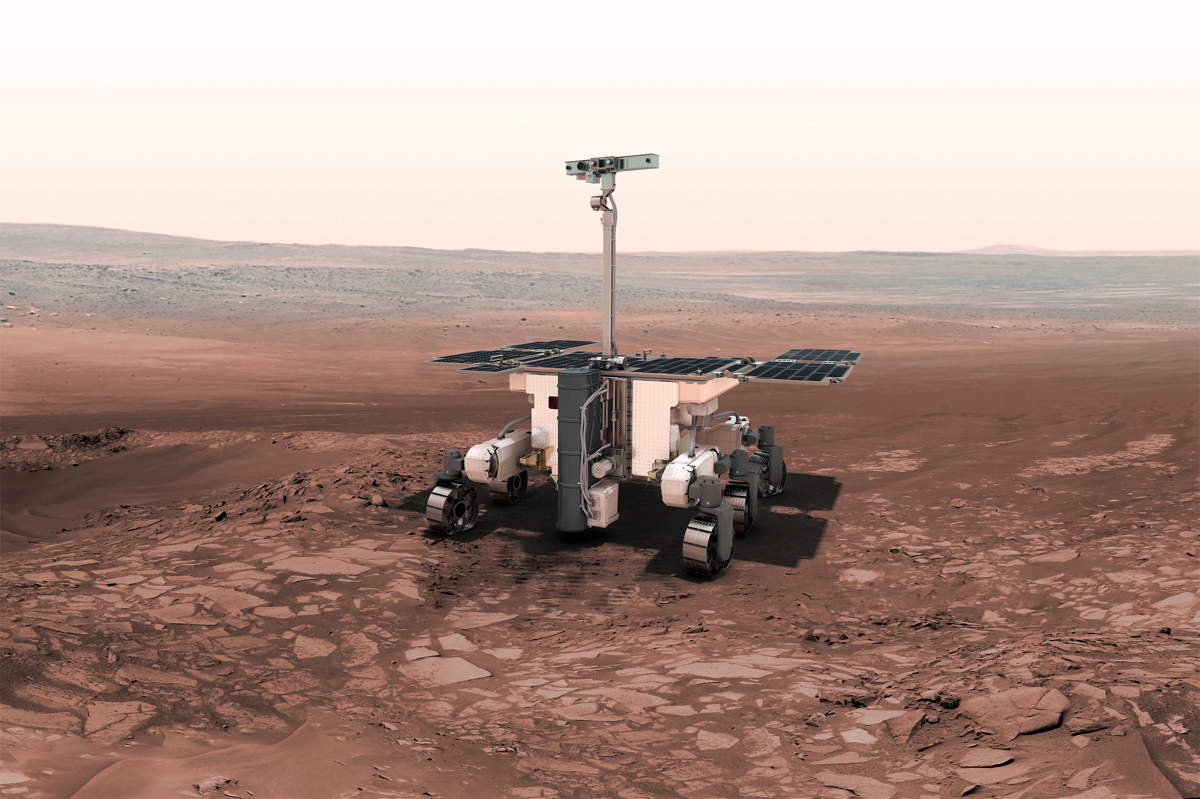

An artist’s illustration of the ExoMars 2018 rover on the surface of the Red Planet.

Credit: ESA

DARMSTADT, Germany —The successful launch of Europe’s first ExoMars mission last week set the stage for a much more ambitious second act: arover landing on the Red Planet. But the timing on that mission may not be so certain.

On March 14, the European Space Agency (ESA) and its Russian partners launched the ExoMars 2016 missi on, an orbiter and lander that serve as a precursor to a full-blown rover slated to launch as early as May 2018. But funding issues and technical delays could push that ambitious follow-up mission to 2020.

Rolf de Groot, ESA’s coordinator of robotic exploration, told Space.com that it’s going to be “very challenging”to have the mission fully prepared for its 2018 launch window but that program managers will know soon whether they’ll have to start seriously thinking about a 2020 launch instead. [ExoMars Takes Flight: Amazing Launch Photos ]

“We have very clever engineers trying to see if we can try to reform some of the testing procedures and cut corners, without adding additional risk to the mission,” de Groot said. “I would say, within the next month, the decision will be taken to see whether we can go forward with 2018. I’m still hoping that we will be able to find ways to do it.”

In regard to a possible delay for ExoMars 2018 ,Thomas Reiter, a former astronaut and ESA’s director for human spaceflight and robotic exploration, also said, “We are currently doing a very intense review of the project, and we will do everything to maintain the launch date.”

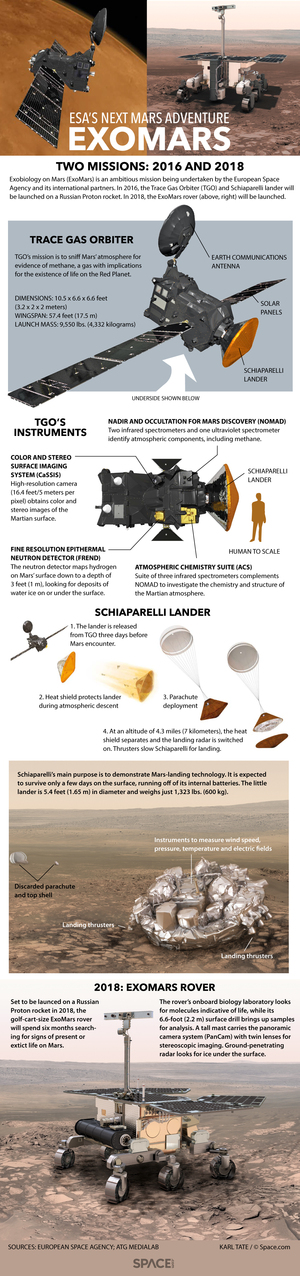

The European Space Agency’s ExoMars project involves an orbiter, lander and rover, launched on two separate Proton rockets (infographic)

Credit: by Karl Tate, Infographics Artist

A long time to get off the ground

ExoMars has experienced several delays —and several mutations —since it was conceived more than a decade ago as one of the flagship missions of ESA’s Aurora program, an initiative intended to pave the way for human missions to Mars .

The rover was originally supposed to launch in a single mission on a Soyuz rocket with a more modest payload, de Groot said here at ESA’s Space Operations Centre during a presentation for the March 14 launch event. In 2005, the rover got bigger, and the mission became “Enhanced ExoMars .”The mission split in two—with a Mars satellite and rover to launch separately —as the project expanded and NASA signed on as an international partner in 2008. [How Europe’s ExoMars Mission to Mars Works (Infographic) ]

NASA had planned to provide the Atlas launcher for both missions, as well as its sky crane delivery system —like the one it used in its Mars Curiosity mission —to safely land the ExoMars rover. But then, in 2012, NASA dropped out of ExoMars because of budget issues, and ESA had to reconfigure the mission yet again.

The Russian space agency, Roscosmos, stepped in as a partner and agreed to provide the Proton rockets to get ExoMars off the ground. The Russians contributed some of the instruments in the scientific payload for ExoMars 2016, but the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) and the landing capsule Schiaparelli were largely European products, Reiter said. Roscosmos will have a much bigger role in 2018 —which will require a lot more technical and industrial coordination between the partners.

“The carrier module and the rover will be built in Europe, but the lander is a Russian product,”Reiter said. “That means that the cooperation between the Russian industry and the European industry will significantly intensify.”

Sometimes, Russian space managers have a different style than their European partners. For instance, de Groot pointed out, the Russians don’t like to work with backup launch dates, whereas that’s a normal practice for the Europeans.

A Russian Proton-M rocket launches the European Space Agency’s ExoMars 2016 mission toward the Red Planet from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on March 14, 2016.

Credit: Stephane Corvaja/ESA

Space News reported that ESA Director-General Johann-Dietrich Wörner even used 2020 for the date of the ExoMars rover launch during his slide presentation when speaking at Russia’s Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan for the recent launch. Wörner reportedly said he didn’t want to “disappoint people if, under certain circumstances, we have to move it.”

Launch windows to Mars only open about every 26 months, though sometimes, there are two windows in short order. ExoMars 2016 was supposed to blast off during a three-week launch opportunity in January, but it was delayed until the March 14-25 window after a problem with the lander was discovered.

“We were extremely lucky that, this year, there was a double window,” de Groot said.

If ExoMars misses its opportunity in 2018, it would have to launch in the summer of 2020 —the same window in which NASA plans to send its next life-seeking rover to the Red Planet as part of its $1.5 billion Mars 2020 mission.

Funding could be another challenge. The European budget for the entire two-phase mission is 1.3 billion euros ($1.5 billion). Reiter said that although the major part of ExoMars has already been funded, ESA members will have to decide on some additional funding that would be needed to complete the mission at the next meeting of their ministerial congress in December.

But ESA might need the funds sooner. According to Space News , ESA officials have said ExoMars needs another 200 million euros ($220 million) by this June at the latest, to pay for the 2018 hardware production and operations.

Onlookers watch a demonstration of a prototype Mars rover for the European Space Agency’s ExoMars 2018 mission during a 2010 industry presentation in Turin, Italy.

Credit: Thales Alenia Space-Italy

Clearing the way for a rover

The outcome of ExoMars 2016 when it arrives at the Red Planet in mid-October could also have implications for the rover mission.

ExoMars 2016 will be conducting some important science experiments in its own right. The TGO could help scientists better understand where methane, a possible sign of life, comes from on Mars. And Schiaparelli, a 1,300-lb. (600 kilograms) landing capsule, will measure environmental conditions and, for the first time, Mars’sandstorm-fueling electric fields, after it touches down on the Red Planet’s surface.

But the most important goal of ExoMars 2016 might be proving out technology that will make a future rover landing possible —an unprecedented task for Europe.

It’s notoriously difficult to land on Mars . Just look at spacecraft like NASA’s Mars Polar Lander, the British-built Beagle 2 and Russia’s Mars 2, all of which made the long journey from Earth to Mars, but ended up losing communication with Earth after rough landings.

The major obstacle to a successful landing is Mars’thin atmosphere. When you land a spacecraft on a body with no atmosphere, like Earth’s moon, you only need to fire a landing engine; this will bring you smoothly and softly to the surface, said ExoMars lander engineer Olivier Bayle. By contrast, a thick atmosphere like the Earth’s provides enough friction for spacecraft to slow down and make a soft landing with the help of a parachute (like Russia’s Soyuz capsules, which deliver astronauts back to the ground).

But Mars ‘ atmosphere isn’t thick enough to slow down spacecraft so that they don’t crash. To put Schiaparelli—and eventually, a rover — on Mars, ESA will use a combination of a heat shield, a big parachute and landing engines, all of which need to work perfectly in a daunting sequence of events that Bayle explained here in a presentation.

Schiaparelli will separate from TGO three days before reaching Mars. Then, it will go into hibernation mode to save its battery life, only waking up an hour before landing. The heat shield will help the spacecraft withstand temperatures of up to about 3,100 degrees Fahrenheit (1,700 degrees Celsius) as it decelerates from about 12,400 mph to 930 mph (20,000 km/h to 1,500 km/h).

After about 3 to 4 minutes of this fiery entry, the lander’s parachute will deploy and the front shield will be released. Then, the radar altimeter beneath the lander will measure the spacecraft’s velocity and altitude in relation to the Martian surface below. Using that data, Schiaparelli will decide when it’s time to separate from the parachute and will start firing its landing engines.

“All the systems have to run like clockwork to make sure we have a successful landing,”Bayle said.

And testing those technologies will be key to sending the much more complicated second mission to land the ExoMars rover and surface platform safely in the Russian-built descent module. What’s more, TGO will be a crucial link in relaying information from the rover back to Earth.

If the entire mission is successful, the scientific payoff could be huge.

The ExoMars rover stands apart from previous Mars rovers mostly because of its drill. Previous drilling robots on Mars have been able to reach depths of only about 4 inches (10 centimeters). By contrast, the ExoMars rover will be able to extract samples of dirt from up to 6.5 feet (2 meters) below the surface, where ESA officials hope to have a better chance of finding life that’s been spared by brutal solar and cosmic radiation on the Martian surface .

Follow us @Spacedotcom , Facebook and Google+ . Originally published on Space.com .

Comments are closed.