NASA’s Voyager mission launched in the 1970s. Today, it’s making history as it conducts new science. But how are two spacecraft from the ’70s not just surviving, but thriving farther out in space than any other spacecraft has been before?

A Little Mission Background

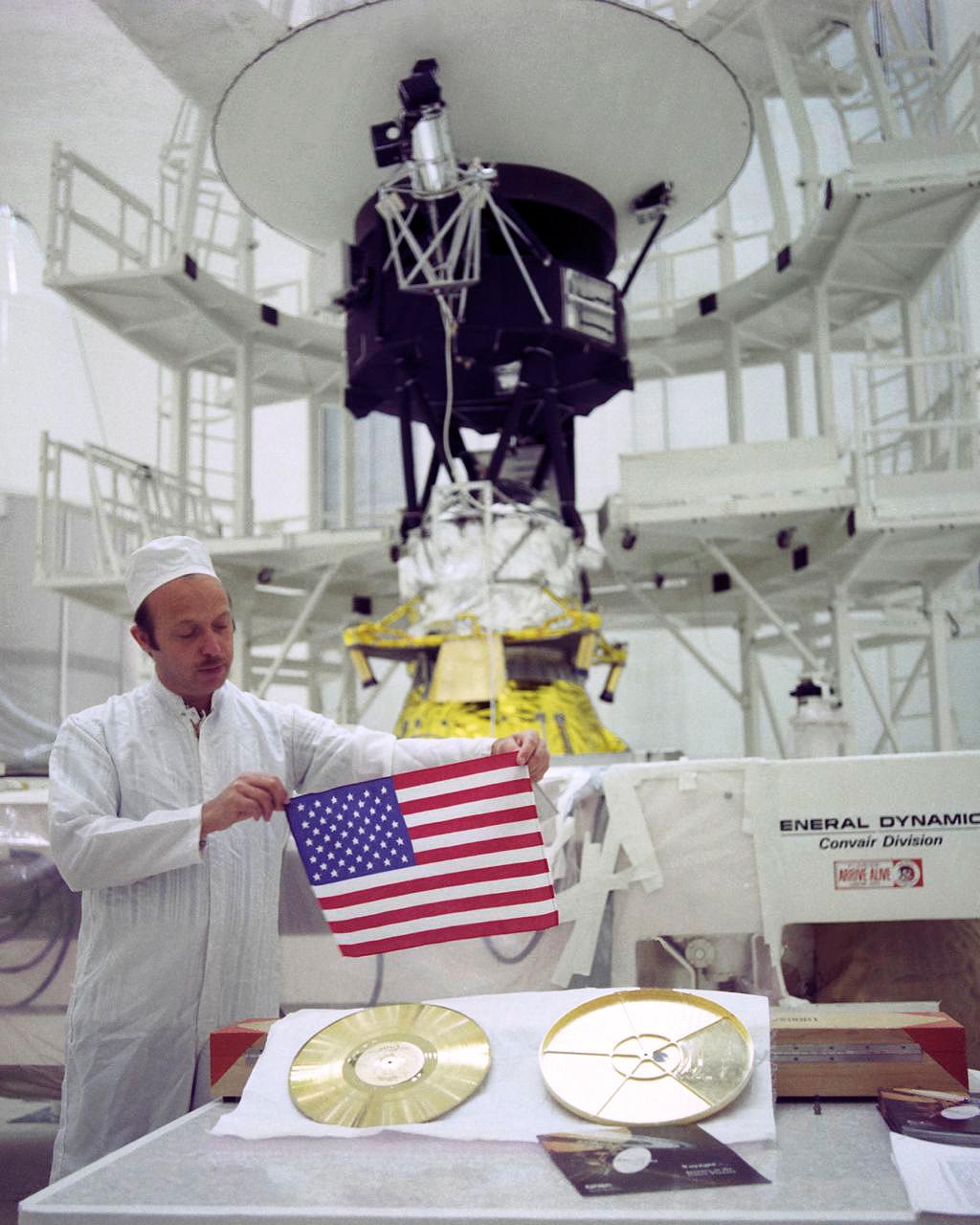

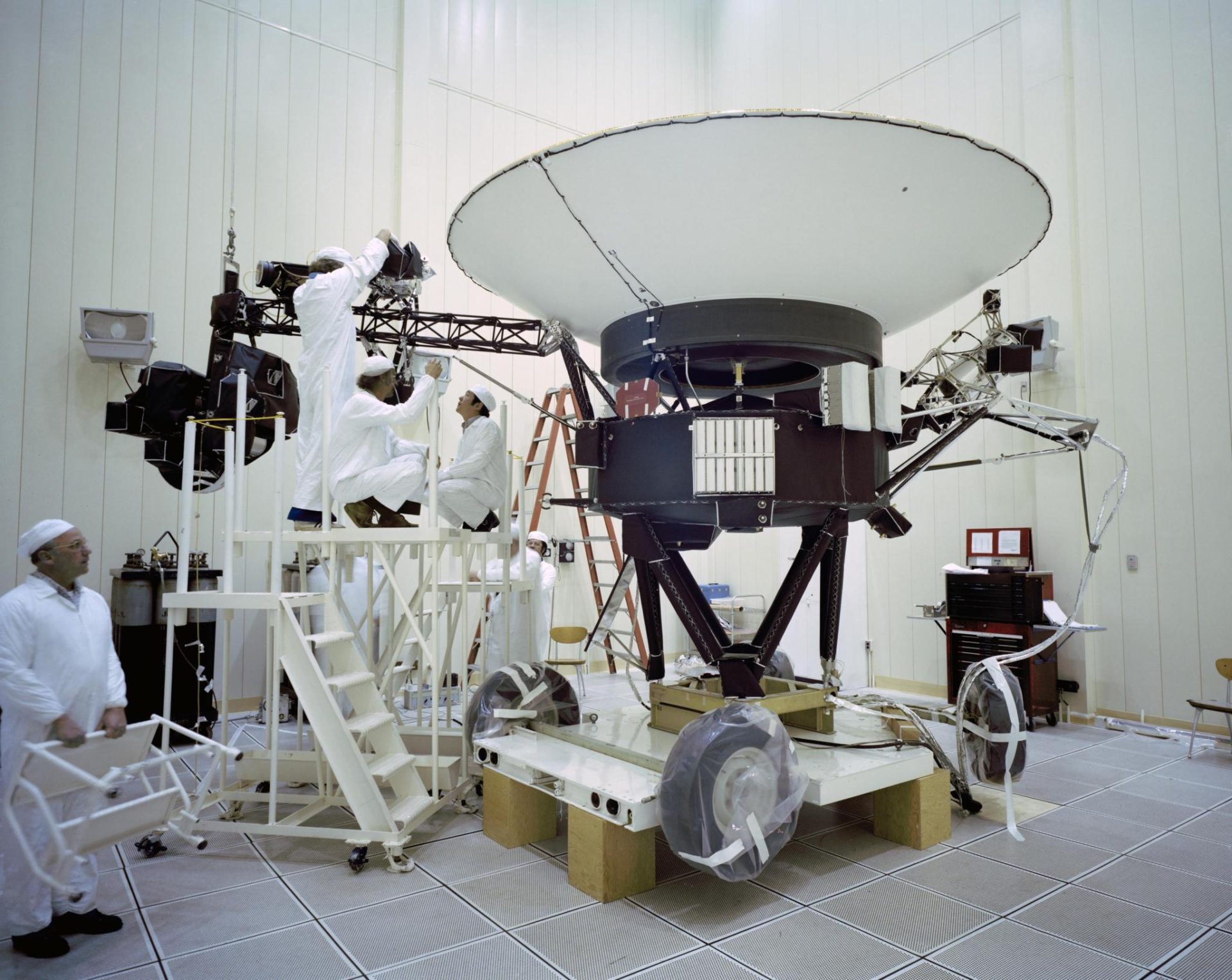

Voyager is a NASA mission made up of two different spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, which launched to space on Sept. 5, 1977, and Aug. 20, 1977, respectively. In the decades following launch, the pair took a grand tour of our solar system, studying Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune — one of NASA’s earliest efforts to explore the secrets of the universe. These twin probes later became the first spacecraft to operate in interstellar space — space outside the heliosphere, the bubble of solar wind and magnetic fields emanating from the Sun. Voyager 1 was the first to enter interstellar space in 2012, followed by Voyager 2 in 2018.

Today, Voyager continues not just because it can, but because it still has work to do studying interstellar space, the heliosphere, and how the two interact. “We wouldn’t be doing Voyager if it wasn’t taking science data,” said Suzanne Dodd, the mission’s current project manager and the director for the Interplanetary Network at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

But across billions of miles and decades of groundbreaking scientific exploration, this trailblazing interstellar journey has not been without its trials. So, what’s the Voyager secret to success?

In short: preparation and creativity.

We Designed Them Not to Fail

According to John Casani, Voyager project manager from 1975 to launch in 1977, “we didn’t design them to last 30 years or 40 years, we designed them not to fail.”

One key driver of the mission’s longevity is redundancy. Voyager’s components weren’t just engineered with care, they were also made in duplicate.

According to Dodd, Voyager “was designed with nearly everything redundant. Having two spacecraft — right there is a redundancy.”

“We didn’t design them to last 30 years or 40 years, we designed them not to fail.”

John Casani

Voyager Project Manager, 1975-1977

A Cutting-Edge Power Source

The twin Voyager spacecraft can also credit their longevity to their long-lasting power source.

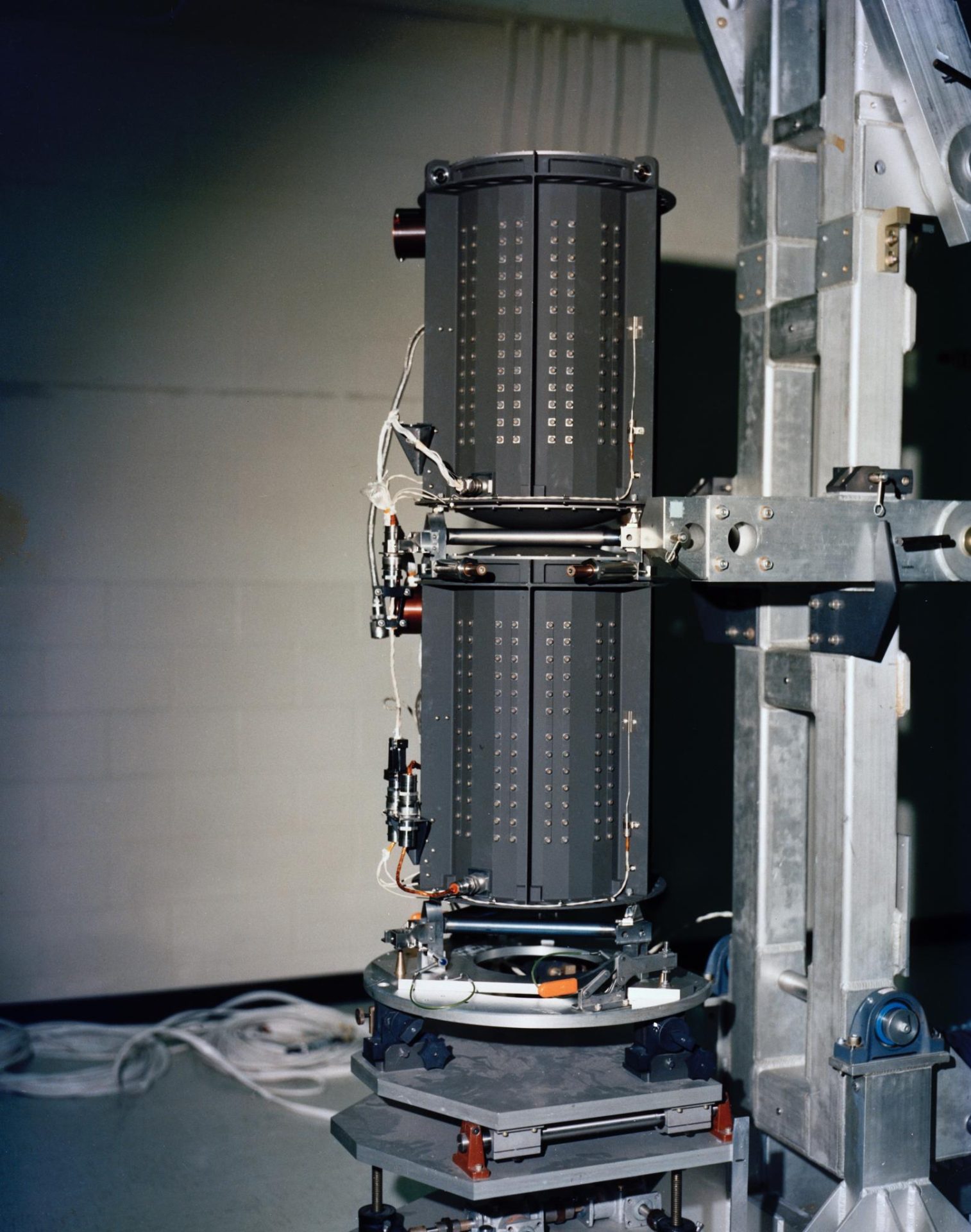

Each spacecraft is equipped with three radioisotope thermoelectric generators. These nuclear “batteries” were developed originally by the U.S. Department of Energy as part of the Atoms for Peace program enacted by President Eisenhower in 1955. Compared to other power options at the time — like solar power, which doesn’t have the reach to work beyond Jupiter — these generators have allowed Voyager to go much farther into space.

Launched in 1977, the Voyager mission is managed for NASA by the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California.

Voyager’s generators continue to take the mission farther than any before, but they also continue to generate less power each year, with instruments needing to be shut off over time to conserve power.

Creative Solutions

As a mission that has operated at the farthest edges of the heliosphere and beyond, Voyager has endured its fair share of challenges. With the spacecraft now in interstellar space running on software and hardware from the 1970s, Voyager’s problems require creative solutions.

Retired mission personnel who worked on Voyager in its earliest days have even come back out of retirement to collaborate with new mission personnel to not just fix big problems but to pass on important mission know-how to the next generation of scientists and engineers.

“From where I sit as a project manager, it’s really very exciting to see young engineers be excited to work on Voyager. To take on the challenges of an old mission and to work side by side with some of the masters, the people that built the spacecraft,” Dodd said. “They want to learn from each other.”

Within just the last couple of years, Voyager has tested the mission team’s creativity with a number of complex issues. Most recently , a fuel tube inside of Voyager 1’s thrusters, which control the spacecraft’s orientation and direction, became clogged. The thrusters allow the spacecraft to point their antennae and are critical to maintaining communications with Earth. Through careful coordination, the mission team was able to remotely switch the spacecraft to a different set of thrusters.

These kinds of repairs are extra challenging as a radio signal takes about 22 ½ hours to reach Voyager 1 from Earth and another 22 ½ hours to return. Signals to and from Voyager 2 take about 19 hours each way.

Voyager’s Interstellar Future

This brief peek behind the curtain highlights some of Voyager’s history and its secrets to success.

The Voyager probes may continue to operate into the late 2020s. As time goes on, continued operations will become more challenging as the mission’s power diminishes by 4 watts every year, and the two spacecraft will cool down as this power decreases. Additionally, unexpected anomalies could impact the mission’s functionality and longevity as they grow older.

As the mission presses on, the Voyager team grows this legacy of creative problem solving and collaboration while these twin interstellar travelers continue to expand our understanding of the vast and mysterious cosmos we inhabit.

Read More

- The Story Behind Voyager 1’s Pale Blue Dot

- The Story Behind Voyager 1’s Family Portrait

- Pale Blue Dot Poster

- Voyager 1 Mission Page

- Voyager 2 Mission Page

Comments are closed.