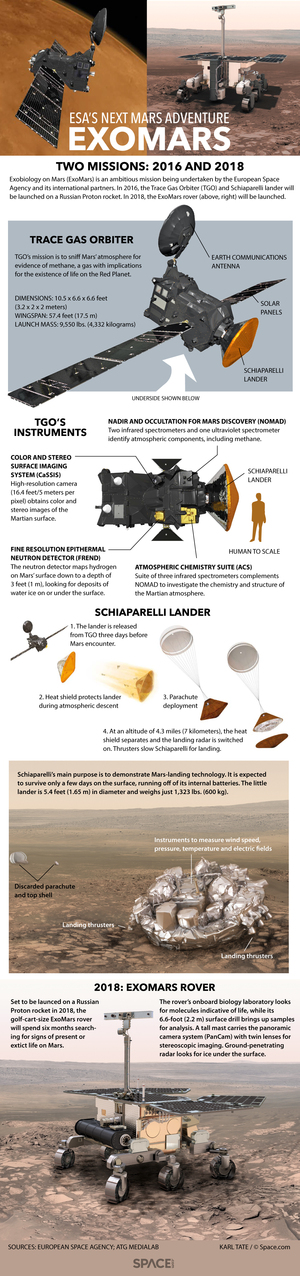

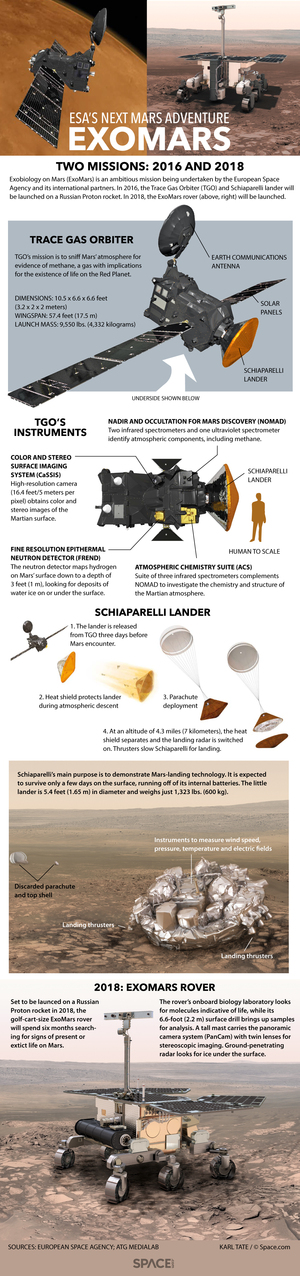

Artist’s illustration of Europe’s ExoMarsTrace Gas Orbiter releasing the Schiaparelli landing demonstrator near Mars.

Credit: ESA

A new Mars mission launching Monday (March 14) aims to kick off a new European program of exploration — and reboot Russian dreams of working at the Red Planet.

Russia hasn’t had any sort of Mars success since 1989, when the Soviet Union’s Fobos 2 mission obtained orbital observations prior to a failed landing. The European Space Agency (ESA) has operated the Mars Express orbiter since 2003, but it hasn’t mounted a successful surface mission on the Red Planet yet. (Mars Express carried a lander named Beagle 2, which never phoned home to its controllers after touching down.)

Monday’s launch — which is scheduled to take place from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan at 5:31 a.m. EDT (0931 GMT) — aims to change all of that. The liftoff will initiate the first part of ExoMars, a two-phase Red Planet exploration program led by ESA, with Russia’s federal space agency, Roscosmos, serving as a partner. [Gallery: The ExoMars Missions ]

On Monday, a Russian Proton rocket will blast the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) and a small lander named Schiaparelli on a seven-month journey to Mars. TGO will hunt for methane (a possible sign of life on Mars) from orbit, while Schiaparelli will head to the Red Planet’s surface, to test out entry, descent and landing technologies for the second part of the ExoMars mission — a life-hunting rover that will lift off in 2018.

ExoMars 2016 spacecraft composite underwent encapsulation within the launcher fairing at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on March 2, 2016.

Credit: B. Bethge/ESA

“Establishing if life ever existed on Mars is one of the outstanding scientific questions of our time,” ESA officials wrote in an ExoMars mission description .

“To address this important goal, ESA has established the ExoMars program to investigate the Martian environment and to demonstrate new technologies paving the way for a future Mars sample-return mission in the 2020s,” they added.

The European Space Agency’s ExoMars project involves an orbiter, lander and rover, launched on two separate Proton rockets.

Credit: by Karl Tate, Infographics Artist

Rocky road to Mars

Getting to Mars is hard, as the history of space exploration shows. For example, NASA suffered some high-profile failures in the 1990s, such as the Mars Climate Orbiter and the Mars Polar Lander, which launched in 1998 and 1999, respectively. (NASA’s 2016 InSight mission was also just delayed by two years because of an instrument problem; the new launch date is May 5, 2018.)

ESA had its issues with Beagle 2, and also delayed the launch of the first part of ExoMars by a few months due to issues with the Schiaparelli lander.

But the Soviet Union/Russia have had the rockiest road to Mars. The vast majority of Soviet Red Planet missions failed; the nation achieved just a few successes in the 1970s and 1980s.

And neither of the two Mars missions mounted by Russia (which was born out of the Soviet Union’s 1991 collapse) even got out of Earth orbit. Mars 96 failed in 1996, and Phobos-Grunt bit the dust shortly after lifting off in November 2011.

“The Russian program has had its heart broken over the past 30 years, essentially again and again,” journalist Jim Oberg, an expert on Russian space activities, told Space.com. “That, plus their own budgetary constraints continuing to squeeze their own science budget year after year, gives a whole lot of serious problems over there.”

Stepping stone?

High-profile failures make it difficult to attract and retain young Russian talent for Mars programs, Oberg said. Plus, research-and-development budgets are suffering due to money constraints and an emphasis on building something operational. This leaves an aging workforce that has difficulty building anything beyond 1980s technology, he said.

Oberg praised the reliability of Russian rockets, long a source of pride for the nation. But spacecraft provide a different type of prestige. ExoMars, Oberg said, could serve as a stepping stone, helping Russia build up excitement about, and expertise for, interplanetary probes again.

“This is not just to rebuild their confidence, but to actually earn new confidence in that kind of challenge,” Oberg said. “They’ve had nothing [successful] in this century, and that’s a burden they have to go out from under.”

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace , or Space.com @Spacedotcom . We’re also on Facebook and Google+ . Originally published on Space.com .

Comments are closed.