On the night of Jan. 7, 1610, Galileo Galilei turned his new telescope on the planet Jupiter for the first time, and discovered it had moons.

Credit: Starry Night Software

On the evening of Jan. 7, 1610, Galileo Galilei turned his newly constructed telescope on the planet Jupiter and was amazed to observe three tiny stars in a neat row alongside it, two on the left and one on the right.

Galileo didn’t realize it at first, but these “stars” were in fact moons orbiting the planet. If his telescope had better resolution, he would have seen four moons, because the moons Io and Europa were so close together that they looked like one in his telescope.

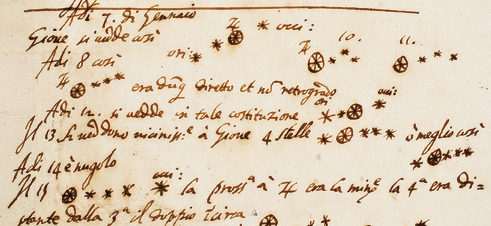

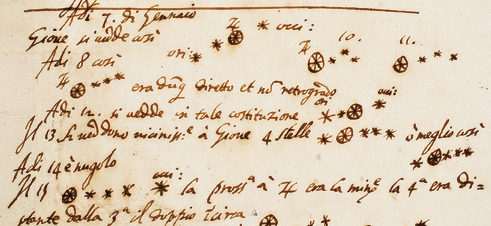

Over the next eight nights, he re-observed Jupiter and quickly realized that these were not background stars, but were four moons in regular orbits, mimicking in miniature the motions of the planets around the sun. In the below facsimile of Galileo’s notes, his observation on Jan. 7 is top and center, Jan. 8 below to the left, Jan. 10 and 11 to the right, followed by Jan. 12 and 13, when he observed the fourth moon for the first time. Jan. 14 was cloudy, but he was able to make another observation on Jan. 15. [Rare Photos: Jupiter’s Triple-Moon Conjunction in Pictures ]

In Galileo’s own hand, here are his first drawings of Jupiter and its moons from January 7 to 15, 1610.

Credit: University of Michigan

On March 13, 1610, 406 years ago this week, he published a book describing this and other discoveries called “Sidereus Nuncius,” or “The Starry Messenger.”

But Galileo wasn’t ready to rest on his laurels. Jupiter was passing behind the sun, in conjunction, on June 25. As soon as it emerged in the morning sky, he undertook a systematic series of observations in order to accurately determine the orbits and periods of the four moons. His Jupiter log resumes on July 25 and continues nearly every clear night for four months. At that point, his Jesuit friends at the Collegio Romano took over the observations through April 1611. They used the diameter of the planet Jupiter as a “measuring stick” to calculate the distances of the moons from the planet.

After Jupiter passed conjunction with the sun on June 25, Galileo watched for it to re-appear in the morning sky, and then began a careful series of observations on July

Credit: Starry Night Software

Nowadays, any skywatcher with even the most basic instrument can replicate Galileo’s observations. Even simple binoculars, if solidly mounted, will show the moons when they are well away from Jupiter, and the lowliest beginner’s telescope will show all four in detail as they shift positions from night to night.

Because the plane of the moons’ orbits is close to the ecliptic, at least three of them pass in front of (transit) or behind (occultation) Jupiter in every orbit. Callisto, the farthest moon from Jupiter, at certain times misses the planet and appears to pass over its north or south pole. When passing behind Jupiter, the moons also pass through Jupiter’s mighty shadow, and so are eclipsed and invisible.

These movements of Jupiter’s moons, and the times of transits, occultations and eclipses, are predicted with great accuracy in the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s “Observer’s Handbook” each year. [The Best Night-Sky Events of 2016: What to Watch for This Year ]

While the moons are passing in front of Jupiter, they also cast their shadows on the planet’s cloud deck below them. These shadows may be observed with telescopes of at least 90mm aperture, provided Earth’s atmosphere is steady. Sometimes two or even three shadows may pass across Jupiter’s face at the same time, but never four. That’s because the orbits of the four moons are in a mathematical relationship which prevents all four from lining up simultaneously.

Over the next two months there are a number of times when two moon shadows can be observed at the same time. Here are some dates and times to look out for double shadows:

- Monday, March 14, 10:22–11:34 p.m. EDT

- Tuesday, March 22, 12:23–2:31 a.m. EDT

- Wednesday, March 23, 7:47–8:59 p.m. EDT

- Tuesday, March 29, 3:00–4:25 a.m. EDT

- Tuesday, April 5, 5:37–6:19 a.m. EDT

- Saturday, May 7, 12:39–1:42 a.m. EDT

If you have a telescope with at least 90mm aperture, mark these times in your calendar, and see whether you can spot the shadows of Jupiter’s moons playing across the giant planet.

Though the shadows are relatively easy to see, the moons themselves are much more challenging. Io and Europa have light-colored surfaces, and usually blend into the background clouds. Ganymede and Callisto are duskier, and often can be seen looking almost as dark as their shadows.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Simulation Curriculum , the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari . Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu . Follow us @Spacedotcom , Facebook and Google+ . Original article on Space.com .

Comments are closed.