<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”34″>

” readability=”34″>

Kepler’s 1,284-Planet Haul in Pics

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

On May 10, 2016, NASA announced the discovery of 1,284 more alien planets by is Kepler Space Telescope, a haul that includes nine exoplanets that might be habitable. See the discovery explained in images here. FIRST: Meet Kepler

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”33″>

” readability=”33″>

Meet Kepler

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

NASA’s $600 million Kepler Space Telescope launched in 2009 to stare at a single patch of the sky. It searches for exoplanets using the so-called “transit method” to look for telltale dips in a star’s brightness caused when a planet crosses in front of the star as seen from Kepler’s location. Astronomers then follow-up Kepler’s finds with ground- or space-based observations to confirm whether a planet actually exists around a given star. NASA’s May 10 announcement included the confirmation of 1,284 alien planets from Kepler’s candidate list.

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”34″>

” readability=”34″>

Exoplanets in Habitable Zones

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

From NASA: Since Kepler launched in 2009, 21 planets less than twice the size of Earth have been discovered in the habitable zones of their stars. The orange spheres represent the nine newly validated planets announcement on May 10, 2016. The blue disks represent the 12 previous known planets. These planets are plotted relative to the temperature of their star and with respect to the amount of energy received from their star in their orbit in Earth units. The sizes of the exoplanets indicate the sizes relative to one another. The images of Earth, Venus and Mars are placed on this diagram for reference. The light and dark green shaded regions indicate the conservative and optimistic habitable zone.

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”34″>

” readability=”34″>

Known Alien Planets by Size

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

This NASA graphic shows the number of known exoplanets, categorized by size, as of May 2016. The blue bars are planets known prior to NASA’s May 10, 2016 announcement of Kepler discoveries. The orange bars represent the 1,284 newly verified Kepler planets unveiled on May 10.

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”31.5″>

” readability=”31.5″>

Exoplanet Discoveries by Year

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

The search for exoplanets was on long before NASA launched its Kepler Space Telescope. This histogram shows the progress of alien planet discoveries since the first exoplanet was found in 1995.

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”35″>

” readability=”35″>

Pie Chart of Kepler Exoplanet Finds

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

From NASA: The pie chart illustrates the results of a statistical analysis performed on 4,302 potential planets from the Kepler mission’s July 2015 planet candidate catalog. For 1,284 of the candidates (orange), the probability of being a planet is greater than 99 percent – the minimum required to earn the status of “planet.” An additional 1,327 candidates (dark grey) are more likely than not to be actual planets, but they do not meet the 99 percent threshold and will require additional study. The remaining 707 candidates (light grey) are more likely to be some other astrophysical phenomena. This analysis also revalidated 984 candidates (blue) that have previously been verified by other techniques.

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”32.5″>

” readability=”32.5″>

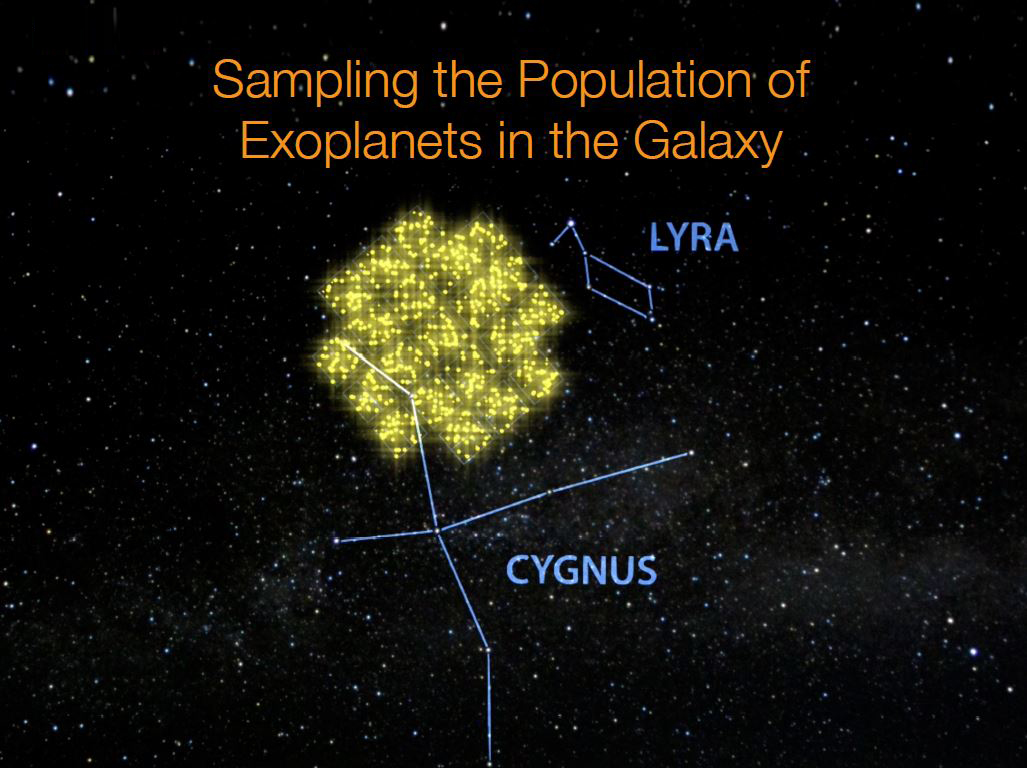

Kepler’s Exoplanet Field of View

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

The thousands of alien planets found by Kepler have all been found around stars in a single patch of the sky between the constellations of Lyra and Cygnus. Kepler basically stares at 150,000 stars for signs of dips in brightness that suggest the presence of an exoplanet.

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”32.5″>

” readability=”32.5″>

A Famous Namesake

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

It’s worth mentioning that the Kepler Space Telescope is named in honor of the 16th-century astronomer Johannes Kepler. From NASA: “NASA’s Kepler Mission was named in honor of Johannes Kepler because he was the first person to describe the motions of planets about the Sun in such a way that their positions could be precisely predicted.”

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”35.5″>

” readability=”35.5″>

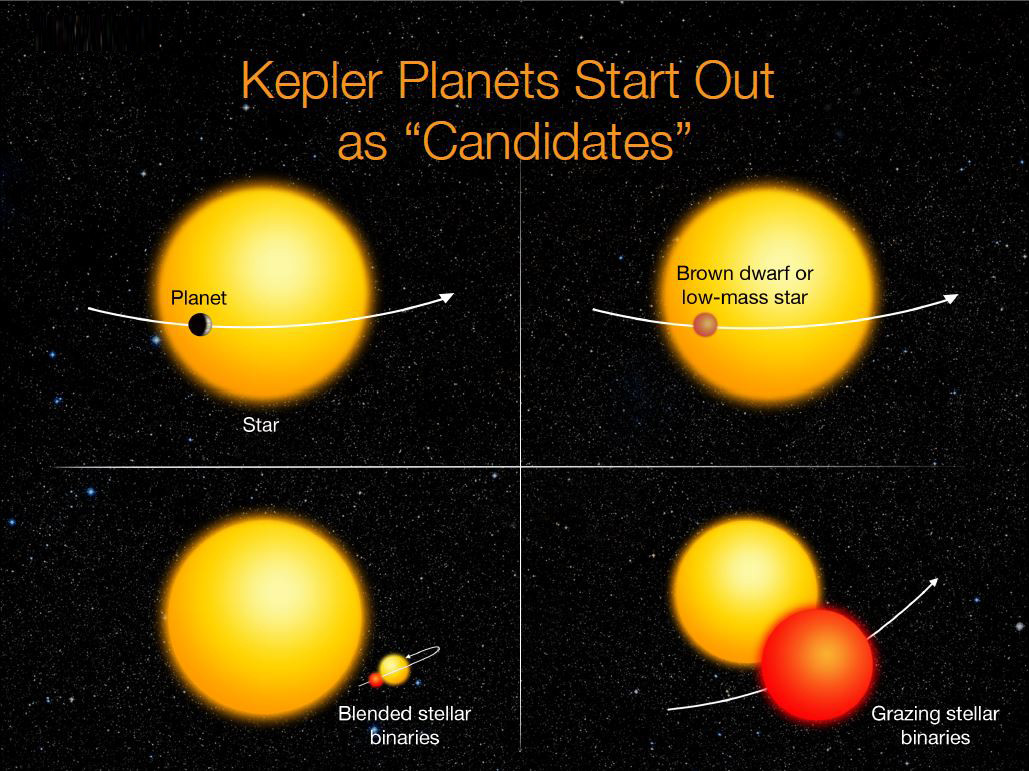

Transit Method Needs a Double-Check

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

Kepler uses the “transit method” to detect dips in a star’s brightness caused when a planet crosses in front of (or transits) the star, as seen by Kepler. The method is not infallible, and requires verification to make sure the brightness dip was caused by an actual planet, and not something else like a smaller, dimmer star. In fact, the May 10 announcement of Kepler’s 1,284 newly confirmed planets also included the declaration that 428 other Kepler candidates were likely one of these false-positives.

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”32.5″>

” readability=”32.5″>

Verifying Candidate Planets

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

After Kepler finds a candidate exoplanet, the planet’s existence has to be verified by follow-up observations. Scientists use different methods and instruments (some of them shown here) to make those checks.

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”32.5″>

” readability=”32.5″>

Kepler vs. Ground-Based Telescopes

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

Verifying Kepler’s planet finds is a huge challenge because the space telescope can see fainter stars than those typically targeted by ground-based telescopes. This NASA chart shows that the candidate planets of Kepler (shown in orange) tend to be smaller and orbit fainter stars than those observed by ground-based telescopes (in blue) using the same transit method.

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”34.5″>

” readability=”34.5″>

Is It Really a Planet?

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

NASA explains Kepler’s new validation method as thus: “A new statistical validation technique enables researchers to quantify the probability that any given candidate signal is in fact caused by a planet, without requiring any follow-up observations. This technique uses two different kinds of simulations– both simulations of the detailed shapes of transit signals caused by both planets and objects, such as a star, masquerading as planets (left diagram), and also simulations of how common imposters are expected to be in the Milky Way galaxy (right diagram). Combining these two different kinds of information gives scientists a reliability score between zero and one for each candidate. Candidates with reliability greater than 99 percent are call ‘validated planets.'”

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”34″>

” readability=”34″>

Kepler Space Telescope: 2009-2017

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

NASA’s initial mission for the Kepler Space Telescope ended in May 2013, when the second of four reaction wheels failed and limited the telescope’s vital precision pointing capability. In May 2014, NASA approved a follow-up K2 mission, which runs through September 2017. The k2 mission aims Kepler at stars along the plane of Earth’s orbit (the ecliptic).

<div data-cycle-pager-template=” ” readability=”32″>

” readability=”32″>

The Future of Exoplanet Discovery

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle

The Kepler Space Telescope is just one in a long line of missions and projects aimed at finding planets around distant stars. Future space telescopes and new techniques promise to push the limits of astronomical discovery.

” readability=”34″>

” readability=”34″>

” readability=”33″>

” readability=”33″> ” readability=”34″>

” readability=”34″> ” readability=”34″>

” readability=”34″> ” readability=”31.5″>

” readability=”31.5″> ” readability=”35″>

” readability=”35″> ” readability=”32.5″>

” readability=”32.5″> ” readability=”32.5″>

” readability=”32.5″> ” readability=”35.5″>

” readability=”35.5″> ” readability=”32.5″>

” readability=”32.5″> ” readability=”32.5″>

” readability=”32.5″> ” readability=”34.5″>

” readability=”34.5″> ” readability=”34″>

” readability=”34″> ” readability=”32″>

” readability=”32″>

Comments are closed.