Mercury appears to experience quake-like activity as it shrinks, making it tectonically active just like Earth, scientists say.

Mercury may still rumble with earthquakes, or “Mercuryquakes,” according to a new study of cliffs on the planet’s surface.

The finding suggests that Earth is not the only tectonically active planet, the authors of the research say.

Mercury is the smallest and innermost planet in the solar system, and was a mysterious world until NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft became the first probe to orbit Mercury in 2011. The only other visits it received were the flybys made by NASA’s Mariner 10 probe more than 40 years ago. [Photos of Mercury from NASA’s Messenger Spacecraft ]

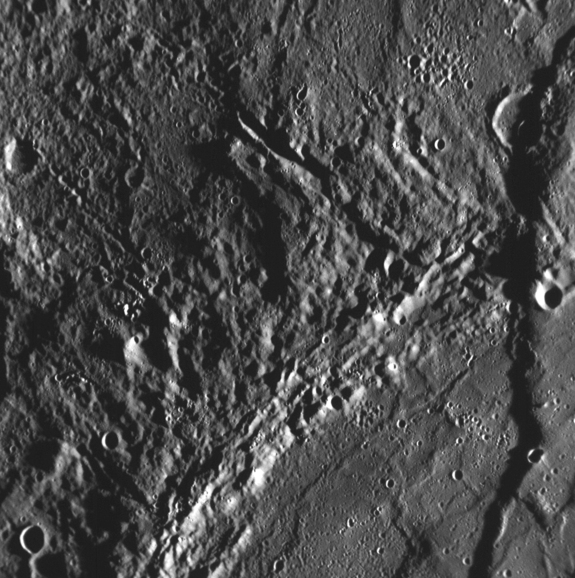

Mariner 10 discovered a vast array of large fault scarps , or cliffs, on Mercury, and MESSENGER revealed that the largest of these scarps are more than 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) long and more than 1.8 miles (3 km) high.

Long, steep cliffs (scarps) on the surface of Mercury hint at the possibility that the planet experiences earthquakes, or “mercuryquakes.”

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington

Fault scarps form when rocks are pushed together and thrust upward along faults — or fractures — in a planet’s crust. The most widely accepted model of the origin of the large fault scarps on Mercury is that they are essentially wrinkles that formed on the planet’s surface as that world’s heart cooled over time, leading Mercury to shrink in size . Previous research suggested that Mercury may have contracted by about 1.8 to 8.7 miles (3 to 14 km) in diameter.

During the last 18 months or so of the MESSENGER mission, the spacecraft descended closer to Mercury, helping it to snap pictures of its surface in greater detail. Now scientists have discovered small fault scarps that are less than 6 miles (10 km) long and only up to dozens of feet high.

The new analysis shows that the pristine appearance of these small fault scarps suggests that they are less than 50 million years old. Previous research suggests that older features would get pockmarked with craters from meteoroid impacts.

The young nature of these small fault scarps suggests that Mercury is still experiencing quakes that are likely driven by the continued cooling and shrinking of the planet, said study lead author Thomas Watters, a planetary scientist at the Smithsonian Institution’s Center for Earth and Planetary Studies in Washington.

“These faults on Mercury have got to be accompanied by seismic activity,” Watters told Space.com.

Comparable scarps are seen on the moon , and four seismometers set up on the moon by the Apollo missions detected moonquakes reaching up to magnitude 5 on the Richter scale.

“We might expect shallow seismic events of a comparable level on Mercury,” Watters said. “We might even see events significantly greater than magnitude 5 with the older, larger scarps.”

The seismometers on the moon detected 28 shallow moonquakes ranging from about magnitude 1.5 to 5 on the Richter scale between 1969 and 1977.

“Mercury has the potential for many more earthquakes than the moon, since it’s contracted a lot more than the moon has,” Watters said.

It remains a mystery how a planet as small as Mercury has not already cooled down completely and lost all its heat. Instead, Mercury remains warm enough to keep shrinking and to have a molten outer core that has supported a magnetic field for billions of years.

“The way that terrestrial bodies like Mercury, Earth and even the moon have evolved thermally is emerging as one of the puzzles that researchers need to solve in planetary science,” Watters said.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Sept. 26) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi . Follow us @Spacedotcom , Facebook and Google+ . Original article on Space.com .

Comments are closed.