Pages from Jonathan Fisher’s 200-year-old journal reveal sunspots during the 1816 “year without a summer.” Most of the journal is written in code, but the scientific observations are not.

A 200-year-old journal found in a small house in Maine gives a rare look at the sun’s face ages ago.

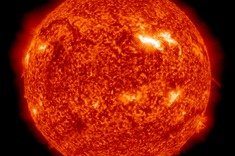

The aged pages are among a mere handful of early American solar observations, and they could shed significant light on the solar activity cycle , astronomers said.

In 1816, the Northern Hemisphere experienced what many refer to as the “year without a summer .” Jonathan Fisher, a Congregational minister who studied extensively at Harvard University before becoming a reverend, thought that perhaps the sun was to blame. So, in June 1816, he began to make detailed drawings of sunspots in his journal. [Photos: Sunspots on Earth’s Closest Star ]

“Fisher is a special case to me, because he was born just too early,” Michael McVaugh, a historian at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told Space.com by email. McVaugh and solar scientist William Denig, of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), authored a paper reporting the discovery of sunspot drawings in Fisher’s journals.

“He would have been happy as a scientist,” McVaugh said. “But science as a career in the new U.S. didn’t start to exist until 1815 or so, whereas he went to Harvard in 1789 and graduated in 1792, soaking up a lot of science and mathematics along the way but never dreaming that he would or could be anything else other than a committed and devoted Congregational minister.”

A huge eruption

In April 1815, Indonesia’s Mount Tambora erupted, spewing ash and sulfur dioxide into the air and forming aerosols that kept sunlight from streaming through. The resulting plummet in temperatures led to major agricultural losses in Europe and North America, causing widespread starvation.

According to Denig and McVaugh, gentleman scientists around the world speculated that the sun played the key role in the extreme temperature change, not knowing about the connection between the eruption and the weather. The low number of sunspots present on the sun at the time seemed to strengthen this hypothesis, as the sun was going through the minimum part of its 11-year activity cycle.

“As he was a highly educated man, it is probable that Fisher was aware of the speculated association of the cooler temperatures with sunspots,” the authors wrote in their paper, which was published in July in the journal Space Weather .

Only two weeks after heavy snow blanketed his home in Blue Hill, Maine, in June 1816, Fisher began to sketch the sunspots in his journal. He continued sketching until the summer of 1817, when the weather returned to normal.

“It was the weather that triggered his observations, not the sunspots [themselves],” McVaugh said.

While Europe boasted state and royal observers — such as Sir William Herschel , who made some solar observations that chilly summer — and scores of professional astronomers, the young country across the ocean had not yet built such a community.

“The new U.S. didn’t sponsor science — it didn’t have any money for science and no tradition of valuing it — so a record of sunspots depended on individuals who might be looking at the heavens. And there weren’t many, because science wasn’t a profession to go into yet,” McVaugh said.

Just handful of others in the Americas made sunspot observations prior to 1816, and Fisher is the only person in the region known to have recorded the sunspots from that fateful year. [Solar Quiz: How Well Do You Know Our Sun? ]

Another sample from Jonathan Fisher’s journal.

Credit: Jonathan Fisher Memorial

Hidden in code

Fisher’s journals were not tucked away for centuries but rather displayed proudly at his historical home. But as a young man, he had developed a code that made his journal daunting to crack.

Fisher was born in 1768. When his father, a Revolutionary War soldier, died, Fisher went to live in the home of his uncle, a minister. In 1788, Fisher’s widowed mother scraped together the funds to send him to Harvard, where he studied enthusiastically.

While there, Fisher devised a shorthand code that he used in his journal. The code — which his biographer Mary Ellen Chase wrote, “he always held in high esteem among his accomplishments” (in her 1948 book “Jonathan Fisher, Maine Parson, 1768-1847”) — kept researchers from uncovering the secrets of the journal. Fisher had made the key readily available, however.

0 of 10 questions complete

“It was only in 1940 that someone had the patience to decipher his shorthand and make a transcript of what he had written,” McVaugh said.

McVaugh is a summer resident of Blue Hill, Maine, and a guide at the Jonathan Fisher House . In preparation for a series of talks on the “year without a summer,” he reviewed a nonillustrated digital copy of the translation of Fisher’s journals to draw on the reverend’s remarks.

“Then I decided to look at the originals, which are still in Fisher’s house, and I discovered that he had made these regular drawings of the sun in his journal to help him illustrate a theory he had about the sunspots and their connection to the awful weather,” McVaugh said.

These drawings, now available online at NOAA’s website , provide another way of tracking how sunspots evolved across the sun over time.

“Knowledge of the solar cycle depends on as much information as we can get over extended periods of time,” McVaugh said. “Fisher’s observations contribute to that in new and absolutely unparalleled ways.”

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd , Facebook or Google+ . Follow us at @Spacedotcom , Facebook or Google+ . Originally published on Space.com .

Comments are closed.